What’s next for old office buildings in southern Connecticut?

[ad_1]

The 1970s was the start of a great migration — a corporate exodus from the city to the suburbs.

Experts say the vast movement of Fortune 500 companies from Wall Street and midtown Manhattan to greener pastures in the suburbs literally reshaped the landscape of southern Connecticut, transforming rolling woodland and sleepy town centers into gleaming corporate office parks designed by the leading architects of the era.

But now, many of those corporate parks are flagging; COVID-19 sent workers home from office buildings, in some cases for years. Some companies folded or closed their offices entirely. At the same time, the need for housing has grown as corporate work shifts to more home offices or hybrid schedules that include work-from-home.

“In the last two years, landlords have taken a look at their real estate,” said James Ritman, managing director of the Stamford office of Newmark. The large commercial real estate company said the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a stress test for many office buildings and office parks in the region.

“For the office buildings and parks that weren’t seeing a lot of activity post pandemic, the question is: What’s the next logical or realistic use for this property? It’s probably not office any more,” he said.

Across Fairfield County as a whole, the office vacancy rate stands at about 24 percent as of the first quarter of 2022. In central Fairfield County — which includes Darien, Norwalk and Westport — the rate runs at 31 percent during that same period, among the highest vacancy rates in the U.S.

The term Suburban Office Obsolescence began to trend in commercial real estate reports and MBA circles as early as 2015.

A professor and real estate analyst, Randall Zisler, said this year, “Real estate always obsolesces, but COVID increased the pace.”

Once upon a time in the suburbs

The corporate building boom of the 1970s and 1980s created huge new edifices for imposing corporate headquarters, clad in smoked glass, marble and steel.

Stamford saw more than 1.6 million square feet of office space under construction in 1985 alone.

General Electric Co. went to Fairfield. Danbury welcomed Union Carbide Corp. American Can Co. created an artificial dam on a sprawling site in the north end of Greenwich and built an enormous office complex there.

The moves to southern Connecticut had a simple logic: “Location, location, location,” said Robin Stein, a longtime planner for the city of Stamford.

The region was — and is — well-served by its proximity to New York, Stein said. In Stamford and other towns along Long Island Sound, there were large empty tracts of land, friendly local governments and plentiful access to the kinds of amenities that executives and their employees were looking to enjoy.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

In Greenwich, town leaders were more than happy to create a new office-business district for the American Can Company in 1970 at a site formerly zoned residential, a first for the town. A town planner directed company executives to the 181-acre site off King Street when a search team looking to relocate from midtown Manhattan came calling at Town Hall. A 600,000 square-foot complex later rose there, and 2,300 employees worked in offices adorned with rugs imported from Morocco and suede leather chairs.

Stein also pointed out that the suburban office park boom put work closer to home for many corporate executives. Especially in the case of re-locations to Stamford and Greenwich, company chairmen enjoyed much shorter commutes post-move. Sociologist William Whyte found that the average commuting distance for a CEO was eight miles during that era.

But it was clear even in the 1980s that the huge amount of office space built during the boom years was too much for the market to handle.

Stein said Stamford’s office-vacancy rate was becoming a problem by the late 1970s. At the American Can Company in Greenwich, the parking lot for 1,700 cars was half empty by the early ’80s, according to media reports from the era, and in 1984, the company decided to sell off the property and downsize.

A change in focus

Ritman, from real estate company Newmark, said public officials and developers had to take a close look at what kind of creative and adaptive use might work best for an old office site that was no longer viable as a workplace. “What’s the demand in that market? What will the market allow for? You need to know your audience, and your town, what’s needed in Norwalk versus Stamford. What’s lacking?” he said.

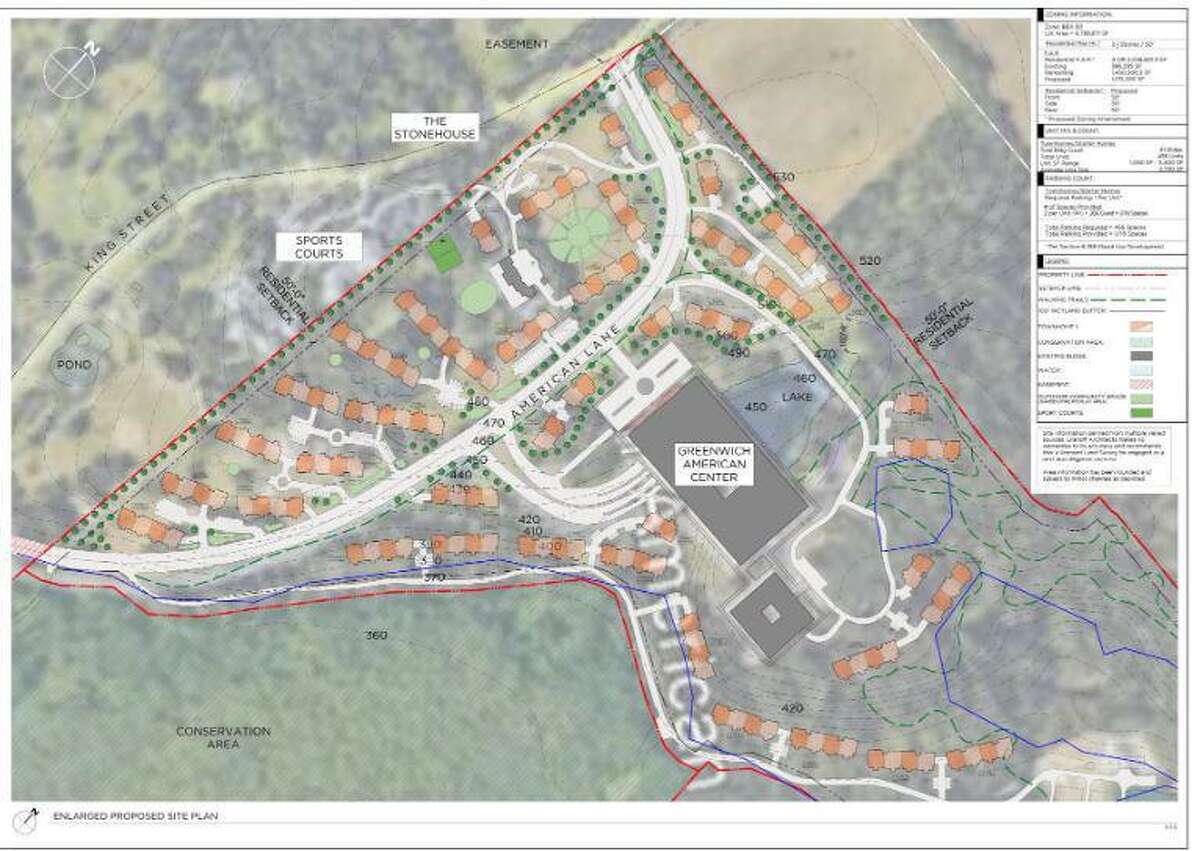

A large residential development is proposed for the old American Can Co. off King Street, now occupied by Tishman Speyer.

Tishman Speyer / Greenwich Planning and Zoning CommissionNow, in Greenwich, Stamford, Danbury, Darien, Trumbull and New Haven, those questions are being asked, and new uses for empty office space have been built or are being proposed. The trend has been accelerating in recent months.

“Given the fact that many people have expressed a desire not to return to the office, or do so on an irregular basis, the people in commercial real estate are now desperate to find revenue generating streams. Everything from apartments to health clubs will give them that opportunity,” said David Cadden, professor emeritus of entrepreneurship and strategy at Quinnipiac University.

Cadden said it was a classic case of supply and demand: “For owners of commercial real estate, it’s an income generating stream, and given the fact there’s a dearth of housing, it will provide housing for people. In Fairfield County, it would seem to be a very viable option. Generating several hundred, or several thousand, units would be very welcome.”

In the north end of Greenwich, a plan by Tishman Speyer, the current owner and occupant of the old American Can property, would build 465 residential units there. Also in Greenwich, 33 upscale residential units were created out of an old office building built in 1981. The Mill in the Glenville section of town, which opened last year, is just one of a number of proposals or conversions from office to retail around the region.

In Stamford, the old General Electric site on High Ridge Road is now the site of of a school and 146 residential units for seniors, Waterstone at High Ridge. The Palmer Hill condominium project on Havemeyer Lane, on the border with Greenwich, replaced the Conair-Cuisinart office park in the 2000s after a lengthy legal battle. Property owners have converted small office buildings near Downtown Stamford into buildings with a handful of studios and one-bedrooms.

In Danbury, the old Union Carbide building, which when it opened in 1982 was the largest office building in the state, has been re-purposed as The Summit, with residences, a fitness club and other commercial uses carved out of the old office building, called a “city within a city” by the development team there. The Summit’s owner wants to supplement the existing space with about 400 apartments.

In Trumbull, 202 apartments were built at a former office site on Oakview Drive. Rivers Edge, an assisted living facility for seniors, was developed at the site of the former United Healthcare building at Route 111 and Old Mine Road.

A developer is currently looking to build housing with up to 88 units on Parkland Drive, an old office site in downtown Darien.

Beside residential redevelopment, developers and property owners have also prioritized turning office space into school buildings.

Danbury officials in March announced that they would turn a former headquarters for the Cartus Corporation into a $164 million “career academy” that prioritizes science and business instruction. The University of New Haven in 2013 bought the one-time headquarters for electrical equipment company Hubbell to house its Orange campus.

The redevelopment trend extends far beyond southern Connecticut. Office complexes around the country are being converted into residences or commercial operations.

According to a market report by Rent Cafe, an industry analyst group, 32,000 apartment units in the U.S. were re-developed from existing spaces over the last two years, with 41 percent of that total converted from office space. Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., led the nation with the most office-to-residence conversions.

Southern Connecticut would be a natural candidate to follow and expand on that trend, say housing and economic experts.

A Darien developer with an extensive background in commercial real estate, Bob Gillon, said some office sites worked better than others for residential conversion.

“The number one challenge is to find the right place,” he said. “It’s location dependent.”

The conversion from a 1985 office building in downtown Darien that he called “functionally obsolete” to a site where housing might be made available to young families or seniors looking to downsize posed a number of difficulties, he conceded.

“But challenges always breed opportunities,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link