Does McKinney Really Need a New Highway?

The best way to find U.S. Highway 380 on Google Maps is to zoom out in satellite view until you can see the entirety of Dallas-Fort Worth’s bulbous, gray-brown mass of sprawl in one frame and then place your finger on the line farthest to the north where it stops. For most of the nearly 90 years since the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials designated the route, Highway 380 was hardly more than a little two-lane road that connected remote farming communities that stretched east from Greenville, straight out across the state and into New Mexico. Today, however, the road is a high-water mark, the coastline of an unbroken sea of urbanization that stretches some 60 miles southward from McKinney to Red Oak. And the tide is rising.

In 2016, residents living along Highway 380 received notices from the Texas Department of Transportation informing them that Highway 380 would soon be transformed into a major freeway—a limited-access traffic artery as wide as 10 lanes in parts. According to the Texas Demographic Center, Collin County’s population is expected to grow from fewer than 800,000 people in 2010 to more than 3.8 million by 2050. Faced with such growth, the state transportation agency determined that a new east-west route would be necessary to move the many millions of cars that would be the inheritance of Collin County’s prosperous future.

But just as traffic engineers tend to see limited-access freeways as the best solution to the challenges of urban growth, people generally don’t want freeways running through their backyards. As TxDOT began rolling out a suite of options for the design and location of the new freeway, the Highway 380 planning process devolved into the most contentious community battle in Collin County history. Deep-pocketed partisans funded social media disinformation campaigns. Entrenched rural residents threatened to send militias to intimidate suburban soccer moms. Subdivision HOA board members accused small-town politicians of cronyism that implicated a beloved beekeeper and owners of a horse farm that serves children with special needs.

That things got so ugly was just one indication that the mess around McKinney is about much more than a road. The expansion of Highway 380 evolved into a battle for people’s homes, their children’s schools, their places of business, and their sense of community and belonging.

In September 2019, I received an email from Amy Limas and Kim Carmichael, two McKinney residents who urged me to come out to Collin County to learn more about Highway 380’s expansion. I had followed the project from the sidelines and knew that, in March of that year, TxDOT had settled on its $2.5 billion preferred alignment for the new road and was embarking on an environmental study, the slowest and quietest phase of the highway-building process, which could take years to complete. Limas and Carmichael, however, promised a new twist in Highway 380’s already jagged tale.

The drive up the Dallas North Tollway can feel like traveling in reverse along the urbanism equivalent of one of those ice core samples scientists pull from the frozen sheets of Greenland to study the history of the climate. Suburban neighborhoods spread out into an unbroken monotony of subdivisions punctuated by big box-anchored strip centers and gleaming glass corporate nodes. It is only when you get close to Highway 380 that the concrete begins to fall away to reveal the source of Dallas’ legendary real estate fortunes: virgin dirt.

In The Path of Progress: (left) Stonebridge Ranch community members Jon Dell’Antonia (left) and Norm Counts don’t understand why TxDOT backs a new freeway alignment that would cost more money and impact more McKinney neighborhoods. (right) Kevin Voigt and his family moved from California to Texas expecting a quiet life in the country only to learn that a Highway 380 bypass would run through their new home.

I meet Limas, Carmichael, and Jon Dell’Antonia, the president of a McKinney homeowners’ association, at McKinney Coffee Company, which sits in a strip center along Highway 380, opposite a rolling expanse of farmland. They spread out documents on a table and race to bring me up to speed. TxDOT’s original plan was to widen Highway 380 in place, but after an economic study projected the astronomical cost of displacing businesses—including military defense contractor Raytheon—the agency devised nine potential routes that would wrap around McKinney. They tried, and failed, to avoid new residential developments. The bypasses TxDOT devised look like octopus arms wrapping around the new subdivisions dotting the rural northern fringe of the city before swooping down to reconnect with the original Highway 380 footprint at the border with Prosper. “They came up with some bypass option that wiped out half our neighborhood,” Limas says. “That’s when we got involved.”

Both Limas and Carmichael live north of Highway 380 in a development called Tucker Hill. It isn’t like a lot of cookie-cutter subdivisions out here. A promotional video calls it “a traditional neighborhood development that captures the distinctive architecture of a historic walkable neighborhood.” The luxury master-planned community of half-million-dollar homes features a mish-mash of architecture, green space for neighborhood concerts, a center square with an art nouveau fountain, and a commercial strip of street-facing retail. “Some people don’t like it because they think we’re like Disney,” Carmichael says.

What Limas liked about Tucker Hill was that it fell within the boundaries of the Prosper Independent School District. She moved in with her husband and two children in 2013. In her spare time, she runs a mothers ministry. Carmichael and her husband moved to Tucker Hill from Frisco, she says, because it was the kind of community where families, empty nesters, and retired couples all feel at home. Neither knew anything about McKinney’s local politics until they learned that a state agency planned to bulldoze part of their community. Limas and Carmichael began to try to figure out what—if anything—they could do about it.

At first that meant showing up to public meetings, where they urged their elected officials to support a new Highway 380 alignment that would cut north of their property, where development was less dense. They understood the road was necessary for the future of the county. They just wanted it to be less disruptive. The problem was those northern parts of the county weren’t unpopulated; they were simply less populated. One of the alignments the Tucker Hill residents supported ran through parts of nearby Walnut Grove, an older, lower-density community of ranch homes on multi-acre lots. Walnut Grove residents didn’t want the new freeway paving their homes, woods, and creeks.

“From the get-go, it was contentious,” says Jay Ashmore, a doctor and Tucker Hill resident who joined Limas and Carmichael in their crusade against the road. “Everyone was kind of protecting their best interest, their homes and neighborhoods. I get that.”

When Tucker Hill homeowners suggested TxDOT look at an alignment that didn’t rejoin the existing Highway 380 right of way until after it crossed the Prosper city line, Prosper residents threatened to kick children from McKinney out of their school district. Limas and Carmichael show me Facebook posts in which someone threatened to send armed militias to Tucker Hill. Other residents had the resources buy ads on social media, and they circulated posts that Limas and Carmichael say spread false information about the highway plans.

None of it intimidated Limas or Carmichael. When northern Collin County residents began showing up to meetings in matching red t-shirts, Limas and Carmichael purchased green t-shirts to outfit their supporters. And the two women started to dig deeper into local politics. In campaign finance reports filed by Collin County Judge Chris Hill, they found a $25,000 donation from Annette Simmons, the wealthy widow of billionaire Harold Simmons, that was made not long after TxDOT initiated its feasibility study. Simmons, they pointed out, owns land east of U.S. Highway 75, near one proposed alignment. They found another suspicious $25,000 campaign donation to Hill from Nathan Sheets, the founder and CEO of Nature Nate’s Honey Co., that was made to Hill’s campaign the day after TxDOT held a public meeting to discuss an alignment that would nearly run over Sheets’ apiaries.

Hill and Sheets did not return requests for comment, but if the donations were intended to sway the eventual design of the road, they failed. In March 2019, after three years of public debate, TxDOT chose a preferred alignment that would run right past Nature Nate’s Honey Co. before encircling Tucker Hill on two sides with a moat of concrete. Limas and Carmichael were devastated, but Tucker Hill residents weren’t the only ones upset with the chosen design. One Walnut Grove resident I spoke to joked that she believed TxDOT tried to demonstrate its lack of bias by choosing the one option that nobody liked. But that wasn’t necessarily true. What Limas and Carmichael couldn’t understand was why TxDOT’s preferred alignment cost $100 million more than the other final design under consideration and disrupted more homes and neighborhoods. The only reason they could come up with for TxDOT’s decision to go with the more expensive option was that it avoided a single property owned by Bill Darling.

In 1987, Darling and his brothers founded Darling Homes, built 34 communities across the northern suburbs, and sold the company to Arizona-based homebuilder Taylor Morrison in 2012. Taylor Morrison continues to use the Darling name, and one of the communities it built under that brand was Tucker Hill. In 2007, Bill and his wife, Priscilla, founded ManeGait Therapeutic Horsemanship, a nonprofit that offers children and adults with disabilities the opportunity to “move beyond their boundaries through the healing power of the horse.” ManeGait sits on Custer Road about a mile north of Highway 380 on 14 acres of pristine pastureland that was in the direct line of one of TxDOT’s final two freeway alignments.

Once ManeGait learned that 380’s expansion could impact its operations, it rallied supporters who flocked to public meetings. That infuriated Limas and Carmichael. Many of ManeGait’s supporters didn’t even live in the area. They learned that Bill Darling was a longtime friend of McKinney Mayor George Fuller’s and that the city had granted more than $300,000 to the nonprofit between 2010 and 2019, even though it technically lies in an unincorporated section of Collin County. And when they dug through the responses to a TxDOT community survey, they discovered many had been addressed to undeveloped lots owned by Traditional Homes, a new homebuilding company started by Darling and his son-in-law Zach Schneider. Darling and Schneider could not be reached for comment.

ManeGait’s involvement in the public process shifted the momentum toward the alignment that would greatly impact Tucker Hill. Once TxDOT learned that its alignment would displace ManeGait, it backed off, citing federal transportation regulations that prohibit projects from displacing communities with disadvantaged or vulnerable populations. Mayor Fuller’s relationship with Darling, however, didn’t stop him from heading out to the horse farm to try to resolve the standoff by making an informal offer to buy out his friend. From the city of McKinney’s perspective, the cheaper and less disruptive route through ManeGait was the most sensible of a number of bad options. Fuller’s offer was generous. McKinney could relocate the farm either through a land swap or by purchasing ManeGait at an above-market price with a no-cost lease-back until the highway construction begins.

“Bill listened to what we said,” Fuller says. “It wasn’t a knee-jerk reaction. He asked to have a couple of weeks to think about that. But after the review, they determined, as an organization, that they did want to stay where they are.”

Even if Mayor Fuller had been able to convince ManeGait to make way for the highway, the new road would still pave over what was supposed to be Kevin Voigt’s forever home. Voigt, a 52-year-old marketing data analyst, relocated to Collin County from Orange County, California, in 2015, with his wife and three children. He found a two-story stone ranch house tucked into a shady grove of pecan and mesquite trees about a mile north of Highway 380, in a subdivision called Bloomdale Farms Addition. It offered what was increasingly rare in California: 5 acres of open land on the outskirts of the quaint historic town that Money magazine named in 2014 “America’s Best Place to Live.”

Not long after Voigt purchased his home, developers began knocking on his neighbors’ doors with offers to subdivide their acreage in hopes of developing future tract housing. Bloomdale Farms has strict deed restrictions that limit the number of homes on its 224 acres to around 24. Voigt and some of his neighbors took the speculators to court and won. “And so it seemed,” he says, “landowners in Texas have real protections.”

That was before Voigt learned about TxDOT’s plans to expand Highway 380. The two alignments that made it to the final stage of TxDOT’s feasibility study looped around some of McKinney’s denser communities, only to run straight through what Voigt’s kids have come to call “our Texas Rock House.” As Limas and Carmichael rallied their neighbors to fill public meetings, Voigt began attending as well, standing on the other side of the room with the McKinney and Prosper residents in red shirts. “We coalesced over a couple of years, in Prosper and McKinney,” he says. “It was kind of a slow boil.”

Voigt has adopted the look of a native Texan, with jeans, cowboy boots, and salt-and-pepper hair swooped back in a rockabilly pompadour. He understands why there was so much contention over the placement of the new road. “Everybody kind of goes into ‘Not in my backyard,’ ” he says.

But when he bought his land in McKinney, he says, he knew he was moving to the edge of a rapidly growing major metropolitan area, and so he did his homework. The city of McKinney has a long-range comprehensive plan that laid out a road map for balancing the consequences of that growth, setting aside areas of the city for more dense new development while attempting to ensure that some of its older, more rural communities could retain their character. Voigt’s acres were supposed to be protected. “They were going to respect rural residential areas,” he says. “Now they discarded that plan.”

It also rubbed Voigt raw that residents who had purchased homes close to Highway 380 now claimed they didn’t want the road in their backyards. “You can’t get a house by the airport and then complain about the noise,” he says. “You can’t buy and build a house—and there are beautiful homes down there—on a highway and then be so shocked when there’s a need to improve the highway. The ox is going to get gored here.”

Voigt says he isn’t against growth and progress in McKinney, but, as with his fight against the speculators, he expected Texas to respect the rights of property owners. “McKinney had put together a vision plan that many people, including myself, had bought property based on what was in that plan.”

When McKinney Mayor George Fuller first ran for office, in 2017, he supported an expansion of Highway 380 within its existing footprint. But he says a subsequent economic analysis of the cost of displacing businesses along that rapidly developing corridor—as well as pushback from Raytheon—forced him to be open to other alignments. Those alignments are not only causing the mayor headaches on the western fringe of the city. An eastern section of TxDOT’s 380 bypass runs perilously close to what Fuller hopes will become one of the city’s major economic engines, McKinney National Airport (TKI, in FAA parlance).

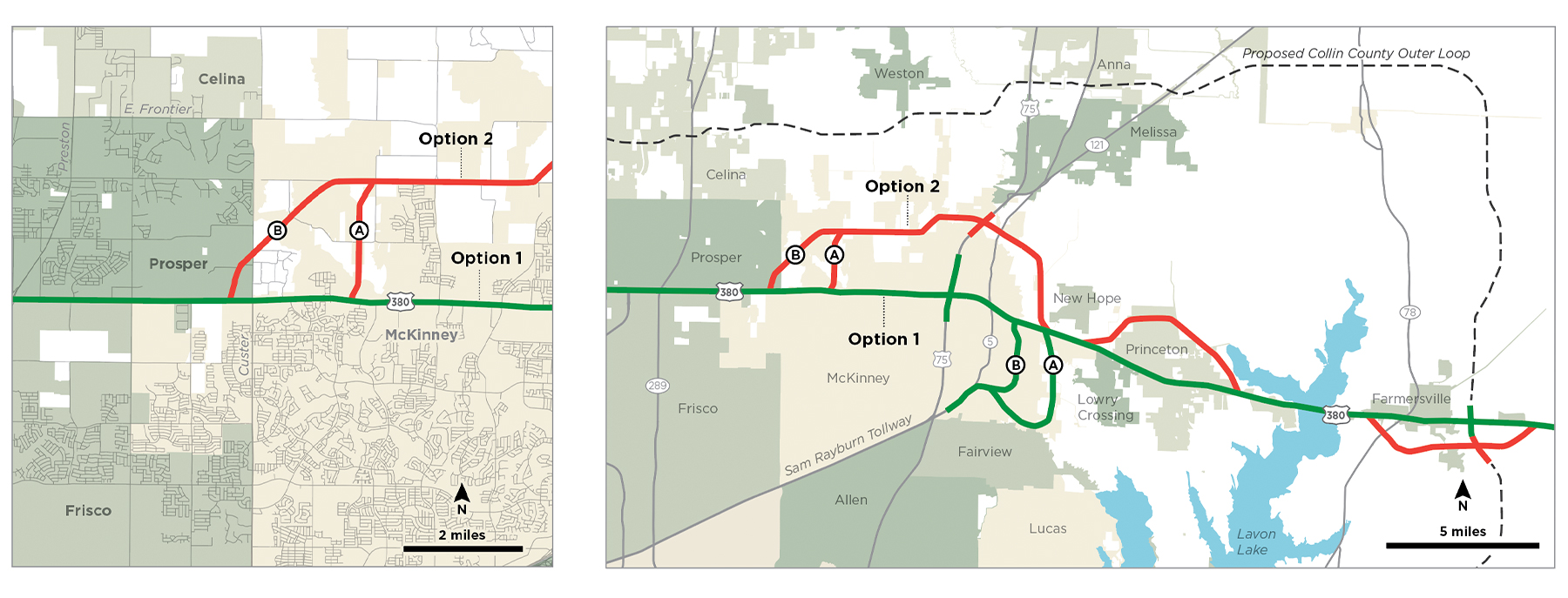

Concrete Spaghetti: Rather than expand Highway 380 in place, TxDOT engineers drew up a series of bypasses designed to avoid McKinney’s rapidly growing footprint. (right) Alignment A twists past several new subdivisions before spilling traffic into the existing right of way south of Tucker Hill. Alignment B passes through the therapeutic horse farm called ManeGait.

Troy Oxford

“For many years, there’s been discussion of passenger service ultimately to be at TKI,” Fuller says. “We’ve got a fixed base operations terminal on the west side of the airport and all our business and corporate travel residents are on the west side of the airport. A terminal for passenger service would be built on the east side of the airport. The last thing we’d want to do is have that highway coming up along the west side of the airport and then having to navigate from there over to the east side for passenger service. That would disrupt everything else that’s going on.”

As Fuller walks through the many complications that come with trying to snake a freeway through a rapidly growing community without disrupting that community, it begins to sound like an impossible situation. I ask him if at any point in the long debate he asked himself if the expansion was really necessary.

“Certainly, I was saying those same things last year,” Fuller says. “I met with TxDOT and had a discussion of parkways versus the highway. But TxDOT came in with their modeling and, at least in their minds—and I guess convinced me as well—that was not feasible to move the traffic that we are going to have to be moving.”

It’s something I hear not only from Fuller but from nearly everyone I speak to about 380. Collin County is growing fast, and without building a new freeway to accommodate that growth, its roads will become a congested nightmare. Even though the highway has created deep divisions, the one thing nearly everyone agrees on is that the freeway must be built.

I find that astonishing. Here is an unbuilt public works project that has already turned neighbor against neighbor, transformed soccer moms into political activists, and driven Californian transplants to become property rights freedom fighters. Residents have flooded the halls of local government to fight for their homes, their families, their schools, and their livelihoods. They are all learning to live under the threat of a looming and massive freeway development project. And yet, throughout the entire ordeal, the freeway—the very agent of destruction they all fear—has never been perceived as the primary threat to their community. Instead, the project planning has mostly turned everyone in McKinney against each other.

It doesn’t make sense. Why should McKinney’s future be tied to a set of binary options? Why should a therapeutic horse farm have to vacate the land and facilities it has built over the last 13 years? Why should a newly built subdivision that has forged a sense of community and ownership be choked off by a highway around its neck? Why should a family staking out a homestead on a few acres of former farmland be forced to move out to make way for a road?

What if the fight over 380 isn’t really about picking winners and losers? What if the reason the 380 battle is so bitter is because no one has been able to figure out how to confront their real enemy?

From an agency perspective, the process to move Highway 380 has been transparent. TxDOT’s website keeps careful track of traffic studies, historic alignment maps, and feedback received at public meetings. It is a remarkable documentation of a seemingly democratic process. Here is a state agency planning a multibillion-dollar highway project with a huge economic impact, and yet it has detailed records of the opinions voiced by every Dick and Jane who happened to stroll into a public meeting to sound off on the project.

If the residents on either side of the battle could come together, they could force a cash-strapped agency to trash the idea of a highway altogether.

But there is one thing that is missing from all of TxDOT’s documentation: a record of the moment in which the state agency decided that North Texas’ projected growth demanded a new freeway bisecting Collin County. The reason that is not available is because the very idea that freeways solve the problem of future growth is baked into every assumption TxDOT makes. Highway-driven regional expansion is an a priori concept of long-range planning in Texas.

Civil engineer and writer Charles Marohn began to question this dogma of transportation planning—which is common in departments of transportation throughout the United States—after working for two decades as a professional engineer and land use planner. In his work with cities and towns around the country, Marohn kept encountering problems similar to the one in McKinney. America’s metro areas have followed a similar pattern of growth since the end of World War II, with older cities transforming into sprawling suburban regions whose expansion is driven by public investment in infrastructure—roads, sewers—that allows for new development of vacant land. But there was a flaw in the model.

Marohn observed that the public sector typically assumes the long-term liability for creating new infrastructure that drives growth. But the kind of growth this infrastructure produces (mostly low- and mid-density suburban housing), while it looks like prosperity, doesn’t generate a tax base large enough to cover the long-term costs of maintaining that infrastructure. “This exchange—a near-term cash advantage for a long-term financial obligation—is one element of a Ponzi scheme,” Marohn writes in an essay titled “The Growth Ponzi Scheme,” for the nonprofit he founded called Strong Towns.

Aspects of Marohn’s idea can be observed in the fight over Highway 380. TxDOT’s plans haven’t kept up with the pace of development in Collin County. Had the state embarked on expanding Highway 380 a decade earlier, McKinney would have been less developed and community pushback less fierce. But TxDOT is struggling to find ways to fund new infrastructure projects throughout the state. In the mid-2010s, as political pressure increased against relying on toll lanes to fund transportation projects, Texas voters approved two ballot propositions that steered oil and gas, sales, and car rental taxes toward highway funding. As the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, those revenue sources are vulnerable to market cycles.

“Quite frankly, Texas doesn’t have anywhere near the money that they need to maintain this stuff,” Marohn tells me when I call him at his home in Brainerd, Minnesota, two hours north of Minneapolis. “We’ve now transitioned into a period of time that should not be about building new stuff. It should be about using what we have in a better way.”

But, as Marohn goes on to explain, making the transition from building infrastructure to maintaining infrastructure is more difficult for counties and municipalities than it sounds. Part of the problem is there is an incentive structure built into the existing regional growth model that can skew the political process.

“The department of transportation comes in and says, ‘We’re going to invest $100 million, $500 million, a billion, $2 billion—whatever the number is—adding capacity,’ ” Marohn says. “What happens is there’s a transfer of public investment into private wealth, and that private wealth shows up in land values.”

When the state invests public money in a road, that road helps drive up the development value of the land it touches. That creates an incentive for large landowners to push for the new roadway projects.

When Limas and Carmichael uncovered huge $25,000 donations to Judge Chris Hill’s campaign from Collin County landowners like Annette Simmons, they didn’t find anything illegal. There is no limit in Texas to the campaign contributions made to a county judge. But they did find evidence of how this incentive structure plays out within the close-knit, closed-circuit world of suburban politics. People like Simmons and Darling forge close relationships with local politicians as they push for continued expansion of the infrastructure networks that can tap the potential of their landholdings. But the residents who eventually come to live in the subdivisions developed on that land are often more engaged with their HOA board than with their council representative. Even Limas and Carmichael admit that, until Highway 380 came along, they hardly knew who their city and county representatives were. That creates a political vacuum.

There is another obstacle. When Collin County residents first heard about TxDOT’s plans to widen Highway 380, they were told the reason for the expansion was that development and growth were already coming—3.8 million people by 2050. If you analyze those population projections according to the parameters laid out by TxDOT, there is no way to disagree with the numbers. But TxDOT’s entire model rests on one key assumption that is never mentioned: regional growth will always proceed as it always has. It is the logic of a Ponzi scheme. Feeling caught in the crosshairs of that inevitability, people living in the path of that presumed progress panic and turn against each other. “The transportation department is the toxic parents,” Marohn says. “And they’re making all the siblings fight.”

Steady March: Between 2009 (left) and 2019 (right), much of McKinney’s vacant land has filled in with development, making it more difficult to thread a freeway through the expanding community.

But there are other models for suburban growth. In fact, McKinney is familiar with them. One of the reasons the city was named the “Best Place to Live in America” in 2014 was because of the success of the revitalization of its historic town square. The restoration of the town historical center showed that investments in walkable communities were not restricted to trendy neighborhoods in large cities. McKinney’s 2040 master plan doubled down on that thinking, drafting a forward-thinking blueprint that imagines a future city balancing the look and feel of a small town center, stable suburban neighborhoods, and protected pockets of rural life. It also looks to create areas of dense residential and commercial growth, such as around the airport, that can expand the city’s tax base while making McKinney less commuter—and infrastructure—dependent.

There are ways to think about McKinney’s future without imagining a Highway 380 crammed with traffic. The development of the Collin County Outer Loop highway project, which is planned to run a mere 5 miles north of Highway 380, could be designed to handle the bulk of inter-regional traffic. TxDOT’s catastrophic congestion numbers assume that the growing population will use its cars in 2050 in the same way we use them today. As the coronavirus pandemic has shown, driving and working patterns may shift in a future filled with remote working. According to the North Central Texas Council of Governments, the region’s municipal planning organization, freeway volumes were down 20 percent, toll road transactions were down 40 percent, and bicycle and pedestrian traffic were up 65 percent during the COVID-19 shutdown, offering evidence that mobility behavior is less static and can shift more quickly than planners often assume.

TxDOT’s traffic projections also assume that cities and counties won’t shift their attitudes about land use to promote new development that doesn’t force residents to rely on their cars for every single errand. The success of McKinney’s town square and newer developments like Plano’s Legacy—and even Tucker Hill’s stage-set walkability—offers evidence that even people living in subdivisions want to spend less time in their cars, not more.

But as Kevin Voigt discovered, land use regulations are only as binding as the political will that backs them up. And as Limas and Carmichael learned, political will in McKinney is often underwritten by people who are deeply invested in the status quo. But what the last three years of Collin County community organizing has shown is that there is potential for a new political voice in Dallas’ suburbs. If the residents on either side of the Highway 380 battle were to come together, instead of passionately attacking each other, they could create enough opposition to force a cash-strapped state agency into trashing the idea altogether.

“The department of transportation has so many projects and they’d rather go to a place that really wants something,” Marohn says. “If the city opposed it, the city could probably stop it.”

Before TxDOT can break ground, it needs to complete an environmental study, which could take another two years. Collin County voters have already approved bond funding for the acquisition of right of way. But with each passing week, the situation on the ground changes. In September, New York-based developer JEN Partners completed one of the region’s largest land acquisitions in 2020, scooping up more than 1,100 acres of McKinney land slated for 3,000 new homes all within a stone’s throw of TxDOT’s preferred Highway 380 expansion alignment. A representative for JEN Partners said the company does not expect the road will have any “material impact on our investment.”

Meanwhile, the immaterial impact of the unbuilt road is weighing heavy on the lives of those living in its projected path. Since the fight over the highway cooled down, Limas and Carmichael have stayed involved in local politics. They supported a candidate from Tucker Hill for McKinney City Council and were asked to serve on a city bond committee. But that increased involvement hasn’t made Limas feel any more empowered. “There’s not a lot we can do,” she says. “We have to wait for the study. We have to wait for our opportunities for public input. And I feel like there’s things going on behind closed doors I will never be privy to.”

Limas’ fear that McKinney’s old-style local politics may still hold sway over the voices of residents is not unfounded. In August, the McKinney City Council overhauled its public meeting speaker rules after another long year of contentious debate, this time revolving around social justice issues and simmering racial tensions that are also at play in this month’s recall vote on McKinney Councilman La’shadion Shemwell. Requests to speak to the Council must now be filed in writing before meetings begin, and written comments will no longer be read out loud into the record. Placards, banners, signs, pennants, and flags are also prohibited at meetings, a rule change that would have dramatically altered the look and feel of the entire 380 debate.

But for now, Limas and Carmichael both say they are staying in Tucker Hill, even though they have heard stories of people moving into the neighborhood without being informed about the pending road project. “It’s crossed our minds,” Limas says about moving. “But I’m on the HOA board. We’re invested, we have a son at the middle school—this is where I’m going to be. It is kind of like, where would we go at this point?”

Voigt is also not budging. He and his family are settling into their new Texas life, even if there is always the feeling that any day he could receive confirmation that the bulldozers are coming for his Texas Rock House. “We’d be brokenhearted for sure if this thing was going to happen,” he says. “But you can’t wake up with that anxiety every day.”

What still gnaws at him, however, is a feeling that the alignment TxDOT selected and is studying still doesn’t make any sense. He is hopeful that the environmental study will explore other options and that there will be another opportunity to argue his case. But the waiting doesn’t sit well.

“I think the frustrating part was when you have developers who are waiting in the wings and you wonder about city decisions,” he says. “If we felt this was the best regional outcome—reasonably the best mobility outcome for north Collin County—we probably could have made more peace with it.”

Write to [email protected] This story originally ran in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline “City on Edge.”